Why protectionist energy policies produce rotten tomatoes

You say tomato, Priyanke Shinde says flow-based market coupling. This week, our Nordic Market Expert breaks down how this complex mechanism helps reduce inefficiencies - ensuring fewer “rotten power tomatoes” in the system. She also explores its impact on electricity pricing and the market.

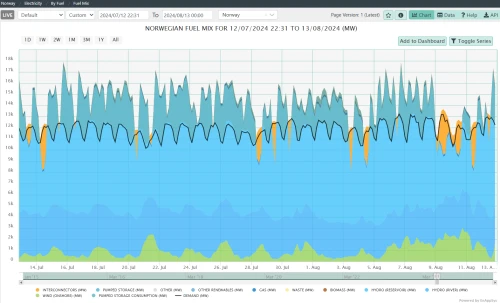

Image: Montel Analytics

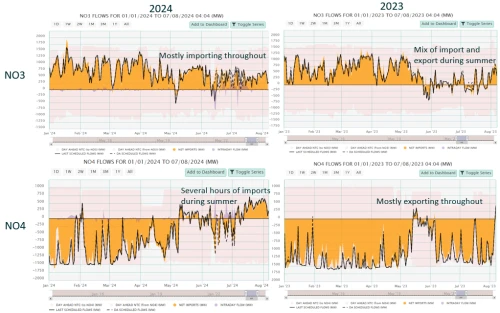

Image: Montel Analytics

Track power flows, volumes and prices across European energy markets