Birthday party paradoxes: an energy expert’s nightmare

Jean-Paul Harreman, Director at Montel Analytics, gives his insight into energy markets paradoxes such as solar in the Netherlands. And why he doesn’t like attending birthday parties anymore.

I used to love birthday parties – food and drink, my Dutch relatives sitting in a circle chatting about weather, football and politics and gossiping about absent friends and family.

When I started working in energy in the early 2000s, this was still common. But something changed around 2016 when people started installing solar panels under a net metering scheme. This allowed Dutch consumers to offset their energy consumption with power generated by their solar panels over a year. This was a flawed arrangement. Solar panels were expensive and with energy prices as they were, it would take 20 years to see investment return.

I knew this but went ahead anyway. Solar panels were costly and the financial benefits were limited, but I have three children and feel an obligation to leave them a liveable world.

Now, back to birthday parties, where the worst question I’m asked is: “Should we go for a fixed tariff of one year, three years or a dynamic price contract?” The best advice requires a mix of market fundamentals, regulation, national politics and geopolitical influences. It’s not as binary as the question suggests. It’s like advising on stocks, bonds and options – not ideal party talk. And if your advice isn’t perfect, you’ll be held accountable at the next party because you’re “the expert”.

The energy transition, the Ukraine crisis and Covid have taken the fun out of birthday parties for me. I go to fewer of them and when I do, I ask people for advice on their field of expertise instead.

I still talk with colleagues about the unintended consequences of well-meaning policies. The energy market is full of paradoxes caused by good intentions, unforeseen outcomes, incomplete information and the varying quality of decision-makers.

Take subsidies, for example. Subsidies help support sectors that are too costly to develop on their own. They make solar panel installation more appealing by reducing investment costs, shortening the payback period and lowering risk.

Too much of a good thing?

But can there be too many solar panels? While they help decarbonise power production, their benefit is limited if too much energy is generated at once and goes unused.

In practice, Europe often sees negative power prices during peak solar production. One might suggest switching off conventional power plants or even the solar panels. But if solar generates revenue even at zero or negative prices, there’s no incentive to switch them off. There’s no cost to keeping them running, although making them controllable would involve costs. My dad asked me how to switch off his solar panels this summer, proof that you can’t avoid all party questions.

The Netherlands’ net metering scheme has resulted in more than 25 GW of installed solar capacity. Peak summer demand is around 15 GW and cross-border capacity is capped at 8.5 GW. Although around 10 GW of this solar is theoretically controllable, it is rarely curtailed.

Subsidies have created paradoxes, undermining the value of power generated, grid stability and investments – without considering the impacts on power purchase agreements (PPAs), balancing markets, ancillary services and transmission issues like congestion.

The key message: subsidies are a simple instrument to stimulate growth. But they need an exit plan. Unconstrained subsidies distort markets, destabilise the playing field and discourage diverse investment.

Net Zero targets

Reaching net zero is vital for saving the planet. But I recently read a politician’s oversimplified claim that doubling our renewable capacity would meet climate goals.

I’ll refer to my uncle to show why this logic is flawed. He owns a flock of sheep, and when one dies it provides about 17kg of meat – enough for his family for three months. So, if around four sheep die every year his family has enough meat.

But what happens when no sheep die for five months, and then bluetongue disease kills four sheep in summer? His freezer can only hold one, so he sells the rest at a loss. Despite theoretically meeting his annual needs, he still experiences shortages and surpluses.

Doubling his livestock doesn’t solve the problem, just as doubling renewable energy won’t solve energy supply issues.

The power market lacks a “fridge”, making these issues even more pressing. While annual renewable generation might meet 50% of demand, shortages and surpluses occur. Doubling capacity can lead to more exports at times of abundance or curtailment when cross-border capacity is maxed out or prices drop below zero.

Volume vs financial balance

At birthday parties, I talk with my cousins about bitcoin and cheap power to build a data centre for mining cryptocurrency. They intuitively understand flexibility: consuming energy during surpluses or storing it for shortages. Their main question is: “Why aren’t there more batteries and storage solutions if continuity and flexibility are the main problems?”

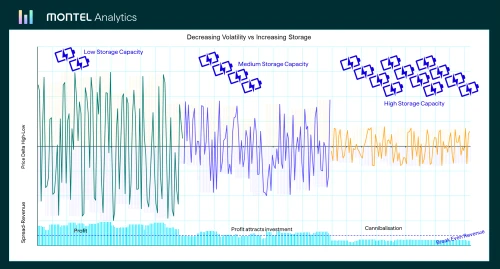

Storage assets can manage the disconnect between supply and demand, but they don’t generate power. Batteries, for example, have efficiency losses and limited cycle lives. They also require significant investment, so they need to generate a return.

As more batteries enter the market, the flexibility problem lessens, reducing returns on investment. Saturation eventually occurs, mirroring the cannibalisation seen with renewables. It’s a delicate balance.

Adding complexity, some market players aren’t driven by financial returns. Transmission System Operators (TSOs), for example, are responsible for grid balance. They always get paid and are overseen by regulators, so they care less about profitability than private investors.

TSOs often publish long-term forecasts for demand, renewable growth and electrification. For example, a recent TenneT study predicted the Netherlands would need 9 GW of battery capacity to balance the grid. Investors, feeding this figure into their models, saw flattened energy prices and insufficient returns.

As a result, no battery projects were financed for a time, as banks refused to back assets expected to lose money.

The longer I work in energy, the more paradoxes I encounter. With experience, I’ve learned to anticipate unintended consequences. So next time someone at a party asks for advice on energy, point them to my posts. It won’t guarantee the right answer, but it will save you from being called out at the next one. You’re welcome.

Understand how policy changes and regulatory incentives affect energy markets

This article originally appeared as a column on montelnews.com