Avoiding the hydrogen hype trap: lessons from blockchain

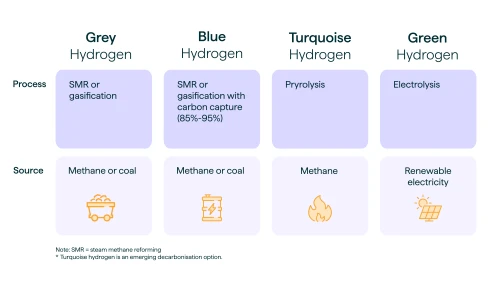

Hydrogen is often called the fuel of the future, but how much of that is hype? Richard Sverrisson, Montel’s Editor-in-Chief, unpacks the pitfalls and promises of this much-discussed gas in the context of Europe’s energy transition.

Follow the latest updates affecting hydrogen markets